We’re always thrilled to have mystery author Lea Wait stop

by for a visit. Today she joins us under her new Cornelia Kidd pen name, which

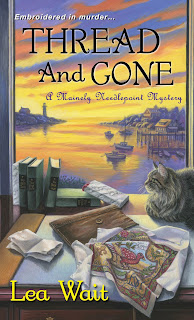

launches her Maine Murder Mystery series. Lea also writes the Mainely

Needlepoint and Shadows Antique Mystery series and historical novels set in

nineteenth century Maine. Learn more about her and her books at her website,

where you’ll find a link to a free prequel of Death and a Pot of Chowder, the first book in her new series. She also

blogs with the Maine Crime Writers.

Salmon Mousse

from Death and a Pot of Chowder

A light lunch? An

appetizer? An hors d’oeuvres with crackers? Mamie’s salmon

mousse will be a hit. This amount will serve four to six, but she suggests you

double the recipe so you’ll have some for tomorrow, too.

This recipe is from

Cornelia Kidd’s Death and a Pot of

Chowder, the first book in the new Maine Murder culinary mystery series,

set on an island off the coast of Maine.

Ingredients:

15-ounce can red salmon (it’s prettier than pink) or 2 cups

cooked salmon, shredded

1/2 T. salt

1/2 T. sugar

1/2 T. flour

1 teaspoon dry mustard

1/2 teaspoon cayenne

2 egg yolks

1-1/2 T. melted butter

3/4 cup milk

1/2 cup rice wine vinegar

1 envelope granulated gelatin dissolved in 2 T. cold water

The day before

serving:

Clean and flake salmon

and put in thin bowl or mold.

Mix dry ingredients in

the top of a double boiler, or a small pan you can cook over another pan. Add

egg yolks, butter, milk, and vinegar. Cook over boiling water, stirring almost

constantly until the mixture thickens enough to stick to your spoon. Add the

gelatin and stir until the gelatin dissolves.

Pour mixture over salmon

and mix gently.

Chill in refrigerator

(not freezer) overnight.

At least 3 hours

before serving:

To remove from bowl or

mold, put bottom of mold in hot water to loosen. Be gentle as you turn mold

upside down on a plate. Then replace mousse in refrigerator for several hours

to ensure mousse will maintain its shape.

Serve with crackers,

thin slices of French bread, cucumbers, olives ... whatever you choose.

Especially refreshing on a hot day.

Death and a Pot of Chowder

A Maine Murder, Book One

Maine’s Quarry Island

has a tight-knit community that’s built on a rock-solid foundation of family,

tradition and hard work. But even on this small island, where everyone knows

their neighbors, there are secrets that no one would dare to whisper.

Anna Winslow, her

husband Burt and their teenage son have deep roots on Quarry Island. Burt and

his brother, Carl, are lobstermen, just like their father and grandfather

before them. And while some things on the island never seem to change, Anna’s

life is about to take some drastically unexpected turns. First, Anna discovers

that she has a younger sister, Izzie Jordan. Then, on the day she drives to

Portland to meet Izzie for the first time, Carl’s lobster boat is found

abandoned and adrift. Later that evening, his corpse is discovered, but he

didn’t drown.

Whether it was an

accident or murder, Carl’s sudden death has plunged Anna’s existence into

deadly waters. Despite barely knowing one another and coming from very

different backgrounds, Anna and Izzie unite to find the killer. With their

family in crisis, the sisters strive to uncover the secrets hidden in Quarry

Island and perhaps, the ones buried within their own hearts.

Buy Links